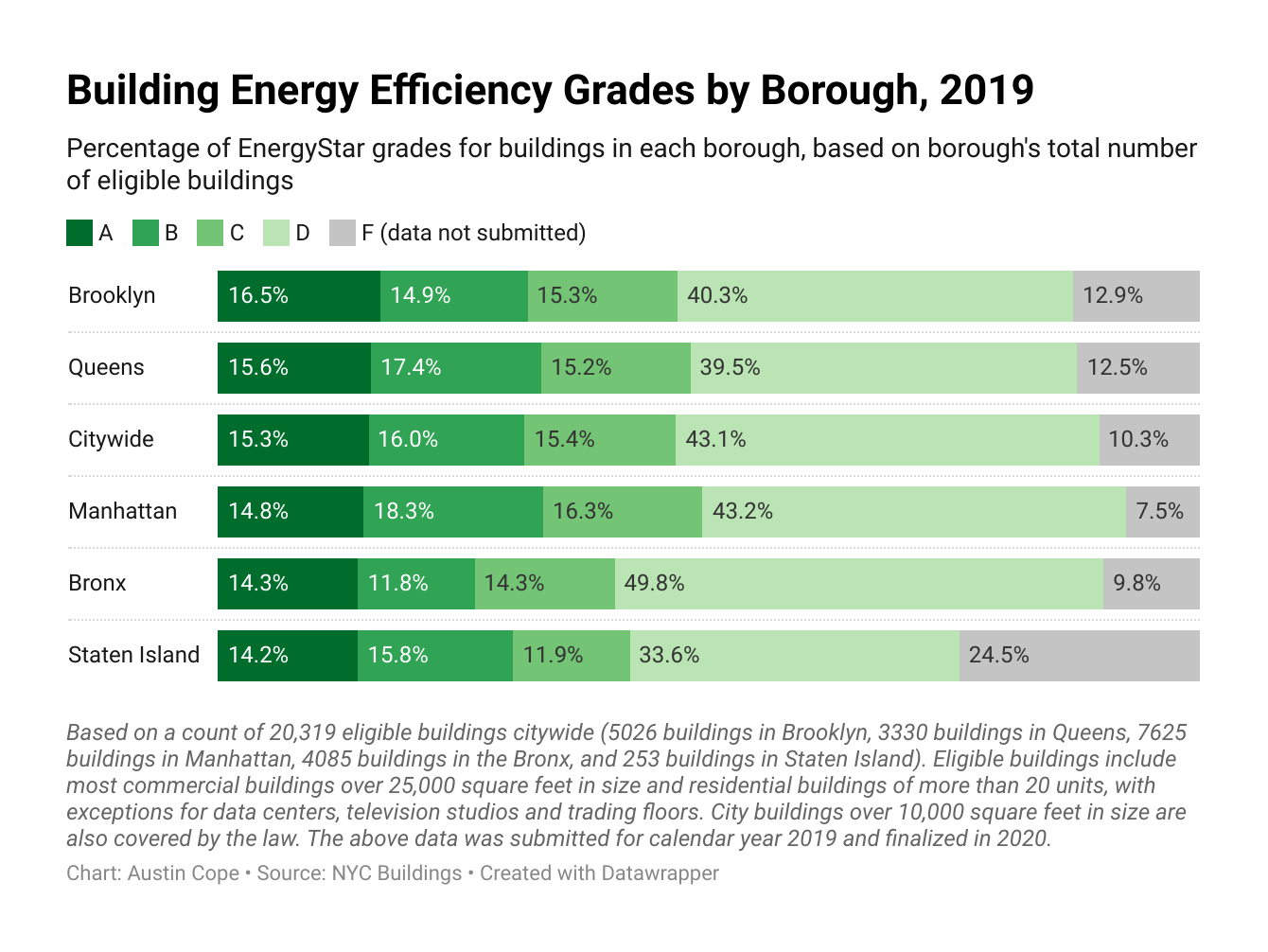

When it comes to energy efficiency, buildings in each of New York City’s five boroughs are almost neck-and-neck.

According to an analysis of 2019 energy benchmarking data collected by the New York City Department of Buildings, over 20,300 buildings across New York City received grades for their energy efficiency in 2019. Each receive relatively similar scores overall.

Proportionally, Brooklyn’s buildings received the highest percentage of “A” grades, but Staten Island, which came in 5th place among the “A’s”, was just two percentage points lower. The Bronx received the most “D” grades, but about a quarter of Staten Island’s eligible buildings didn’t submit their scores at all. Citywide, fewer than half received a passing grade, since about 10 % of buildings received scores of 0 for not submitting their data.

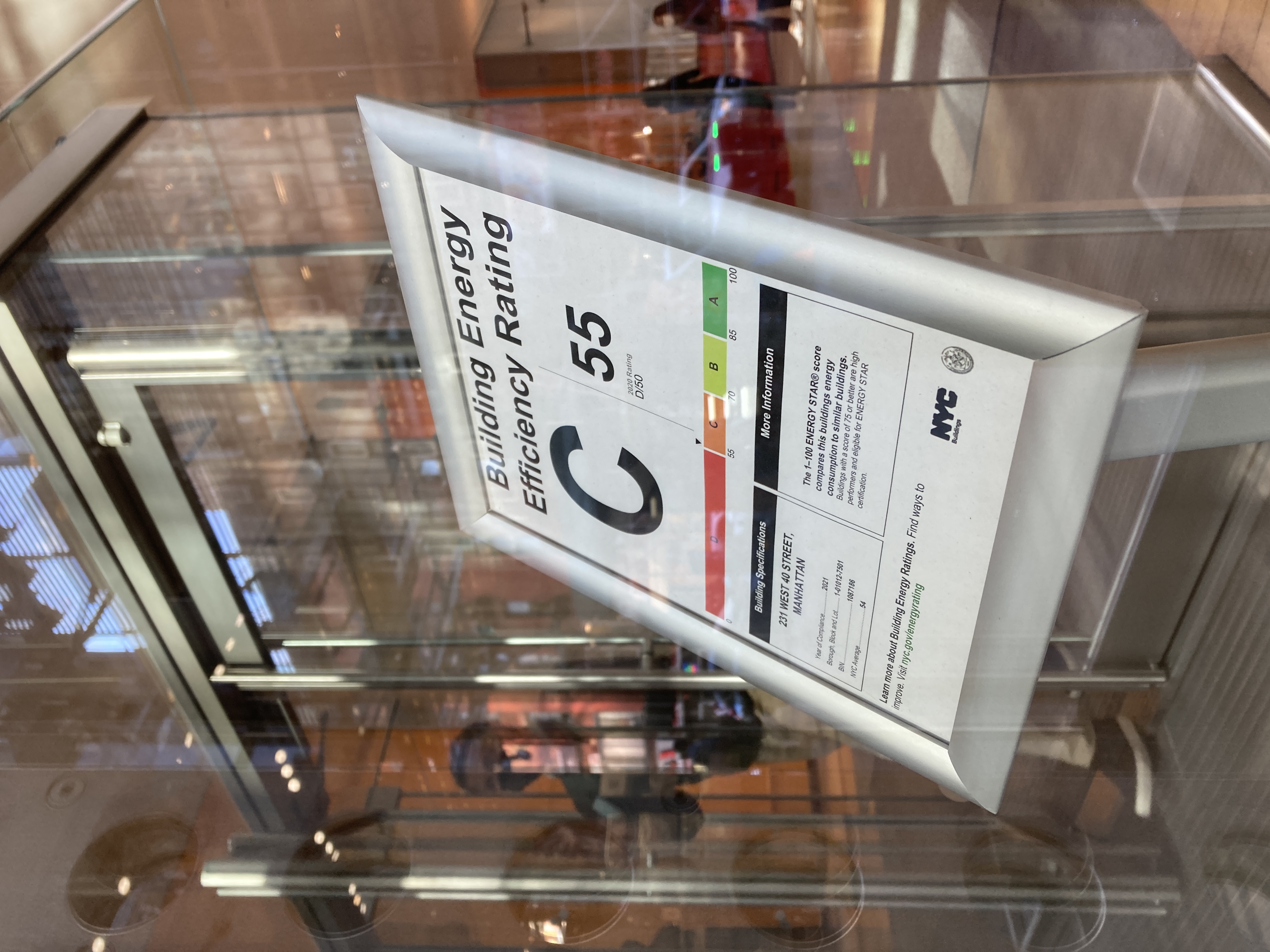

According to city legislation passed in 2016, most commercial buildings over 25,000 square feet in size –excluding data centers, TV studios, and trading floors – must keep track of their energy benchmarking data, and similar laws require them to post these scores publicly on a yearly basis.

Buildings receive their grades from A to D based on Energy Star, a federal program that analyzes building energy use data over the course of one year, then calculates it based on the building’s purpose and use. The score is then ranked in relation to the performance of similarly-sized and purposed buildings across the country. As of 2019, scores above 85 receive a grade of “A,” 85 to 70 receive a “B,” 70 to 55 receive a “C,” and scores below 55 receive a “D”. Buildings that do not submit benchmarking data on time receive a score of 0, or “F”.

However, just because the buildings are posting their data doesn’t mean that we can receive a full picture of their overall sustainability, according to Sean Brennan, Research Director for the Urban Green Council, a New York City-based environmental organization that advocates for improved building efficiency.

“Even if the whole city had A’s on the buildings, you wouldn’t actually know whether or now we’re on track to meet our climate goals, because of the disconnect between total emissions and Energy Star scores,” Brennan says.

The city legislation that requires buildings to publicize their Energy Star benchmarking ratings is not related to another city law setting emission reduction targets to curb climate change in the coming years. While the Energy Star grades analyze how efficiently the buildings are using the energy they generate, they don’t measure the amount of carbon emissions they produce. So, the grades people see when walking through the doors don’t necessarily correlate to a measurement on how well buildings are combatting climate change in general.

But, Brennan says, the grades aren’t misleading – and they're easily understandable for the general public.

“It's a good first step at looking at how a building uses energy, how efficiently it uses the energy in terms of what it's trying to do, and then judging it against its peers that are trying to do the same thing,” he says. “But it’s only a first step.”